The Tour to the power of 10

1920 TdF peloton

At the turn of each decade, the Tour de France has gone through organisational changes and backstage struggles that have variously turned out to be decisive or utterly inconsequential. The journey back in time proposed by letour.fr continues in 1920, with a look at the strong-minded decisions and writings of Henri Desgrange, the director of the Tour de France and chief editor of the newspaper L’Auto. In keeping with a French nation in admiration of its heroes from the Great War and enthralled by the adventures of the first aviators ready to risk their lives for heroics, the former holder of the hour record, who had become a powerful press figure, can also be considered to have made the Tour rhyme with trial and tribulation…

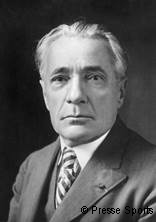

Henri Desgranges

It is a tricky exercise to determine the level of difficulty when designing a race to be demanding, to require its participants to stand out via their bravery and endurance, but to avoid going beyond what is reasonable… This question has been central to debates between organisers, participants, supporters and journalists since the beginnings of sport. Evidently, the notion put forward by Henri Desgrange, the boss of L’Auto newspaper and the Tour in France of the 1920’s, was not troubled with tantrums and bellyaching: his role was to organise a trial, in both the sporting and true sense of the word. It is always possible to discuss which edition of the Tour de France has been the most formidable. The race in 1920 may not necessarily feature at the top of the list, but it definitely included all the suitable ingredients. With a total distance of 5,503 kilometres, it is not the longest in history, though due to only boasting 15 stages, the average daily distance of 367 km is only beaten by the 1919 edition. It should be remembered that the damage caused by the First World War still disfigured the country, with most of the roads made up of potholes, broken cobbles, cracks and ruts… These conditions were not exactly ideal for a bicycle race, especially in light of the fact that the stage starts took place on average at 2 o’clock in the morning.

As if the physical conditions of the race were not tough enough, Desgrange inaugurated a formula aimed at diminishing bicycle brands’ influence on the race and forbid any sort of collusion. The director of the Tour de France was obsessed by this combat, conveyed by strict rules that were applied without the slightest indulgence: “A participant on the Tour de France is placed in the situation of a rider who sets off to train alone without having prepared anything on his route for refreshments. This means: 1. He cannot assist his comrades or competitors in any way and they cannot accept anything from him; 2. On the road, the rider must be responsible for his own refreshments, without having ordered or requested the ordering of anything, and must not receive any help from whomsoever, to the extent by which he is obliged to collect water from the springs or fountains he may encounter by himself. With regard to the bicycle, each rider must complete the Tour de France on the same machine, except in the case of serious accidents. In such a case, he may swap the machine with a cyclist encountered on his route, on the sole condition that the machine borrowed is a different brand to his own”.

Eugene Christophe, 1920 Tour de France

After four stages, the pack was only made up of 48 riders out of the 113 who started the race. The mood was glum, all the more so as the French were palpably dominated by the Belgians.

Thus the scene was set. When the Grande Boucle began at Place de la Concorde on 27th June, the worries about a plethora of punctures became reality. After four stages, the pack was only made up of 48 riders out of the 113 who started the race. The mood was glum, all the more so as the French were palpably dominated by the Belgians. Of course, Henri Pélissier triumphed in Brest and at Les Sables-d’Olonne, but the rebellious temperament of the winner on the Paris-Roubaix and Bordeaux-Paris races in 1919 was hardly to the liking of Desgrange, who did not hold back from writing exactly what he thought about him in L’Auto, the day after he exited the race on the longest stage, between Les Sables d’Olonne and Bayonne (483 km). “Firstly, is Pélissier worse after the war than before? Not at all! (…) He is not worse, but the others are better and the obstacles have become more difficult. Those are some of the reasons. They count for something, but not as much as the reason which dominates all the rest and that Pélissier finely explains as follows: ‘I have money and circumstances that exempt me from undertaking such difficult tasks’. Who can blame him for such a line of thought? At the most, could we ask him why he even starts to undertake them? His mind is no longer what it was in days gone by. He enjoys life, his enthusiasm has been becalmed with age and his heart no longer beats to the devilish rhythm of his beginnings. (…) Moreover, for him the cream is too thick, the spoon stands up in it by itself. He is already morally flabby and cuts a heavy figure, when on the Tour de France it is necessary to be as skinny as a whippet”.

Philippe Thys, 1920 Tour de France

Le 1920 Tour de France continued without Henri Pélissier (who nevertheless enjoyed his revenge over Desgrange in 1923!) and continued to wring out the pack, whittled down to 31 members on completion of the first Pyrenean stage. In his diatribe against Pélissier, the director of the Tour incidentally continued to describe the mental and moral qualities of the valiant champion as he saw them: “And what about his effeminate edginess?! In Morlaix he was not interested, in Brest he was; at Les Sables-d’Olonne he showed intent, but one hundred kilometres further he would not show the slightest bit more. Compare this ‘fair-weather’ attitude with, if I may say, the unswerving will of Christophe”.

Dogged, as often, by bad luck, Eugène Christophe, Desgrange’s favourite, also exited the race, beaten by unconquerable back pains. Nonetheless, it was a similarly tough guy who was victorious in Paris. Philippe Thys became the first three-time winner of the Tour when completing a series started before the war (in 1913 and 1914). He dominated the classification in which the top seven places were occupied by Belgians, after more than 228 hours on the saddle, which is almost three times more than the 83 hours on a bike that Egan Bernal spent last July. It would be interesting to read a portrait of the first Colombian winner of the Tour de France written by the hand of “HD”!