The finish line of the 111th edition will be set up in Place Masséna, Nice, a few pedal strokes from the Promenade des Anglais. It will be the first time that the Tour de France draws to a close far from its home in Paris. However, even before this unprecedented move, the finish of the Grande Boucle had already wandered the Parisian streetscapes and woven the race into the history of several venues. In a four-part series, letour.fr is looking back on the context and highlights of the finishes in Ville-d’Avray, the Parc des Princes, La Cipale Velodrome and, since 1975, the Champs-Élysées.

EPISODE 2: PARC DES PRINCES — THE HOME OF CYCLING

Long before Kylian Mbappé, Zlatan Ibrahimović, Ronaldinho and even Luis Fernandez made the crowds roar with their exploits on the football pitch, the Parc des Princes was already the beating heart of sport in Paris. At the dawn of the 20th century, thousands flocked to the Porte de Saint-Cloud to watch cyclists hurtle around the track of its velodrome. Following the administrative nightmares that plagued the first few editions (see the first instalment), the venue hosted the finish of the Grande Boucle until 1967, for a total of more than 50 editions. Many heroes of a bygone era were crowned in the frothy atmosphere of the Parc des Princes, including the first three-time winner of the race (1913, 1914 and 1920), the Belgian Philippe Thys, who had developed the annoying habit of beating the French in their own race. As L’Auto reported the day after the finish of the 1920 edition, “The fans cheered themselves hoarse and stormed the track as Philippe Thys took his victory lap and the strains of La Brabançonne filled the air. The winner had to complete his glorious march on foot, swimming in a sea of people and struggling to get to the control table to sign the sheets. Law enforcement had their work cut out for them to clear the area of his admirers so he could embrace his friends and family”.

In 1924, another foreigner outgunned the French on their home soil: Ottavio Bottecchia, the first Italian winner of the Tour. The “Bricklayer from Friuli”, second to Henri Pélissier in 1923, was not content to put a whopping 35 minutes into his runner-up, Nicolas Frantz. He dominated the race from A to Z, collected bookend victories and wore the yellow jersey from the first day to the last. Only Nicolas Frantz (1928) and Romain Maes (1935) have since been able to emulate this tour de force.

Leducq and Magne take their final curtain call together

Charles Pélissier was the next rider to set a record for the ages. His older brothers, Henri and Francis, had undeniable talent, but scandal and controversy seemed to follow them wherever they went, often clashing head to head with the race director, Henri Desgrange. The youngest scion of the family took some time to blossom, but once he did, his sheer power dealt serious damage to his rivals, as seen in 1930. Locked in a long-running duel in the sprints with the Italian Learco Guerra, “Charlot” landed a massive haul of eight stage wins, including the finale in the Parc des Princes, where he once again got the best of his Lombard foe. Only Eddy Merckx (1970 and 1974) and Freddy Maertens (1976) have since been able to take eight stages in a single edition.

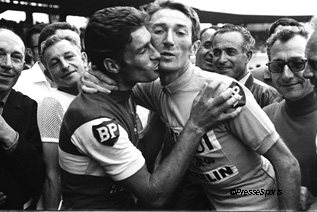

After the end of the 1931 Tour, the Parc des Princes was razed to the ground and rebuilt to host the finish of the race in July 1932. The makeover increased the capacity of the velodrome to more than 40,000 while slashing the length of the track from 666 metres to 454. The 1930s ushered in a renaissance of French cycling. Much like “The Four Musketeers” pursued their swashbuckling exploits on the tennis courts, Les Bleus reclaimed the throne with André Leducq (Tour winner in 1930 and 1932), Antonin Magne (1931 and 1934) and Georges Speicher (1933). Although Gino Bartali won the 1938 Tour, the finish in the Parc des Princes encapsulated the spirit of these halcyon days, as well as the warm ties between this new generation of stars and their devoted fans. “Tonin” and “Dédé”, the two men of the moment, gave the peloton the slip with 55 kilometres to go. It looked like another duel between the two was coming on the track of the velodrome, where Leducq had already raised his arms in triumph in 1927 and 1932, but this time, in their swansong Tour, they decided to show the world the ties of friendship – nay, brotherhood – that bound them, as Leducq put it. The next issue of L’Auto described the raw emotions permeating the stadium: “You’re both swell fellows. I swear, the emotion was real when you barrelled onto the track of the Parc des Princes yesterday. As soon as we saw you ease up in concert at the beginning of the home straight, we realised what was going on. We understood that, after a decade of gallant and chivalrous jousts, this pair of friends had chosen to wrap up together two careers built on fair play, courage, bravery and honour. We were moved to tears. My dear old codgers, how could we ever stop loving you ?”.

Robic turns the 1947 Tour on its head

Following a long hiatus due to World WarII, the first edition after the conflict, held in 1947, was especially fraught with emotions until the very last moment. Ferdi Kübler, René Vietto and Pierre Brambilla zipped around France in the yellow jersey. However, there was a twist at the end: Jean Robic, third in GC, launched a ferocious attack as the peloton exited Rouen and blew the race apart on the roads from Caen to Paris. “Biquet” rolled into the Parc des Princes with 13 minutes in hand over the leader, Brambilla – more than enough to wrest the lead from the Italian and win the Tour without having worn the yellow jersey at any point before the final podium. In his editorial in the next issue, Jacques Goddet heaped praise on the Breton rider, who had not even been among the top favourites: “Fine, we give up! We’d already run out of superlatives to describe this astonishing Tour, but the last day veered deep into fantasy territory. We were expecting a brawl, but we also thought that tradition would prevail, that the cheers would temper the fighting spirit or that Brambilla would rather die on his bicycle than let some upstart steal the win at the eleventh hour. Yet a stubborn, bellicose little Breton who believed in himself wanted to win the Tour and kept trying until he did”.

1948 also saw a historic first, with live television coverage of the finish in the Parc des Princes. Jubilant scenes remained a constant over the years, but disaster struck in 1958. André Darrigade was one of the most admired men in the peloton, with 11 stage wins to his name, including the Parc des Princes stage of the previous edition, in which he had worked hard to propel Jacques Anquetil to the title. The “Landes Greyhound” seemed destined to prevail once again on the final lap, but he rammed headfirst into the secretary-general of the stadium, who had let his excitement cloud his judgment and stepped onto the track. The champion ended up with five stitches, while Constant Wouters had to be taken to hospital, where he died eleven days later.

Before the Parc des Princes morphed into a football stadium, the velodrome hosted one last finish in 1967 as the finishing point of a time trial starting in Versailles. Raymond Poulidor, ninth overall, was no longer in contention for the yellow jersey, but fought on to claim the sixth of his seven Tour stages by 25 seconds over Felice Gimondi and 45 over the fellow in yellow, Roger Pingeon.