The finish line of the 111th edition will be set up in Place Masséna, Nice, a few pedal strokes from the Promenade des Anglais. It will be the first time that the Tour de France draws to a close far from its home in Paris. However, even before this unprecedented move, the finish of the Grande Boucle had already wandered the Parisian streetscapes and woven the race into the history of several venues. In a four-part series, letour.fr is looking back on the context and highlights of the finishes in Ville-d’Avray, the Parc des Princes, La Cipale Velodrome and, since 1975, the Champs-Élysées.

EPISODE 1: VILLE-D’AVRAY — YOU NEVER FORGET YOUR FIRST

The Parc des Princes Velodrome seemed the obvious choice for the finish of the first Tour de France, not least because Henri Desgrange was also the director of the venue, but alas, bureaucratic issues sank that idea in no time flat. Louis Lépine, the prefect of the Seine department, had banned cycling races within the limits of the capital to prevent congestion, so the organisers toyed with the possibility of setting up the finish in Versailles… only for the local authorities to torpedo this option too. After much thought, the town of Ville-d’Avray, on the western outskirts of Paris, emerged as the best back-up solution on the same day that the peloton set out from Nantes in the dead of night for a 471 km stage, the longest of the six that made up that edition.

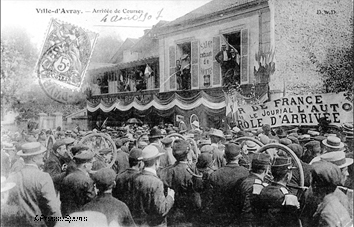

Special arrangements were made to welcome the 21 survivors of the inaugural Grande Boucle. Like every day, the finish line, the point where the timer stops, was right in front of a restaurant, in this case, one that had been renamed from Père Vélo to Père Auto to match the name of the newspaper that organised the event. Maurice Garin had orchestrated a triumphant performance in the first 2,000 kilometres of racing, but he was also determined to culminate his recital on a high note. He romped home in the lead after more than eighteen hours in the saddle. Scores and scores of people had turned out to see the finish. In fact, the ebullient atmosphere caused Jean Fischer to crash against a spectator and hit the deck right when it seemed that he had the stage win in the bag. The next day’s issue of L’Auto provided a vivid description of the scene: “The multitude was getting bigger and more compact with each passing moment. There were people wherever you looked: at the windows, on the roofs, in trees, on bicycles, in cars, riding horses, on foot… It was an unprecedented outpouring of enthusiasm”.

A well-deserved glass of champagne awaited the victor, but the heroes got back on their mounts straight away to parade to the Parc des Princes to receive the rapturous applause of 15,000 spectators.

Fog of war

In 1904, following the same basic concept, but against a backdrop of alleged cheating and underhanded deals that threatened the continued existence of the Tour, Maurice Garin made it two in a row before officials disqualified the top four riders and handed victory to the 19-year-old Henri Cornet, who remains the youngest ever winner of the race to this day. By the following year, tensions had fallen quite a lot, but the organisers of the Tour de France still feared that some riders were up to no good. The final time check was still located outside the capital, but for this edition, the people in charge came up with a novel idea: a secret finish !

Rolling out of Caen in the morning, neither the leader of the race, Louis Trousselier, nor the rest of the field – let alone the public at large – had the slightest idea of where the finish would be decided. The next day’s issue of L’Auto retrospectively pulled back the veil on these preparations: “We camped out at the À la Maison Blanche inn, somewhere between Orgeval and Ecquevilly, from ten in the morning, and watched all the militant sportsmen in Paris zip down the Route de quarante sous in their hunt for the officials in charge of the secret finish. It looks like no-one spilled the beans. Apart from the riders, no-one caught as much as a glimpse of the finish judge and his flag”.

The peloton started to suspect that the end was near as Paris drew closer, but the cyclists were only informed of its exact location a kilometre in advance, when they came across a bare-bones sign reading “1 kilometre to go”. A green flag waved at the last possible moment alerted the field to the start of the final sprint, while a red flag indicated the precise location of the finish. Lucien Petit-Breton and Jean-Baptiste Dortignacq clashed in the mad dash to the line, with the latter prevailing by half a wheel to take his third stage win in the 1906 edition. The riders followed a neutralised section to the velodrome, where another “kilometre” of racing was held to put on a show for fans and acclaim the finishers. However, the main attraction for Parisians was the victory lap of the heroes. The big winner, Louis Trousselier, was in a bit of a hurry.”Why, yes, I won. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’d like to clean myself up”.

1906 saw the return of an actual finish in Ville-d’Avray, followed by a parade and a grandiose award ceremony in the Parc des Princes, where René Pottier was acclaimed as the victor. The town in Hauts-de-Seine has since been a regular fixture on the course of the final stage, coming a couple of minutes before the peloton enters Paris. It made a sensational comeback in 2003 as the start of the finale. Jean-Patrick Nazon would go on to raise his arms in triumph on the Champs-Élysées.