At the turn of each decade, the Tour de France has gone through organizational changes and backstage struggles that have variously turned out to be decisive or utterly inconsequential. The journey back in time continues in 1940: when the country entered the war, Henri Desgrange tried to keep the 34th edition of the Tour alive until spring, but had to resign himself to its cancellation. Before July France was already under German occupation, and Desgrange left the Tour orphaned in August.

According to the tautological principle that you can’t suppress something that doesn’t exist, the 1940 edition of the Tour de France is the only one in history to have been cancelled. Although its detailed route was never published and its dates were not officially announced, its organization was well thought out, envisaged and programmed in the offices of the organizing newspaper, in a France that was nevertheless at war and whose youth had been drafted in September 1939. It would be far-fetched to suspect L’Auto of existing naively in a sports bubble ignoring the major issues in the balance on the battlefield, quite the contrary. From mid-September, the newspaper even assumed a total commitment by changing its title to L’Auto-Soldat, and its editorial line then split between news of the world conflict, analysis of the competitions that continued to take place and news of the champions called up to serve in the armed forces. On 16 September, the headline was accompanied by an unequivocal quote from Voltaire: “Every man is a soldier against tyranny”. It is in this line that Henri Desgrange, who, although seriously ill, did not let go of his pen but distanced himself from sport, multiplied patriotic editorials and caricatures, for example Hitler, whom he described as a “house painter”.

In its services, all the assistants were active and strove to give shape from the very beginning of winter to a cycling season that could also sustain the idea that France continued to live on. In December, discussions began with the heads of the bicycle manufacturers to try to come up with a calendar and invent a new formula. How can a bunch of riders of at the same skill level be formed when most of the riders in the 1939 Tour were fighting? Were foreign cyclists from non-belligerent countries going to be accepted? Who would therefore have their best people available? Where can we get bicycles when the entire industry is focused on the war effort? The debate was launched, and even initiated in the columns of the newspaper, which transcribed the content of the negotiations like a soap opera. Alcyon’s boss was optimistic, but not as determined as Colibri’s: “I’ve come, like all my colleagues, to put a white ball in to get unanimous congratulations,” read the 16 January edition of L’Auto. On the other hand, Genial-Lucifer had more misgivings (“Maurice Evrard felt that in his own opinion the uselessness of certain road races was obvious”, L’Auto of 13 January), and the tone was also very cautious from the head of Dilecta. However, we manage to get everyone to agree year after year on a formula published on 6 February which, among other measures, only admits riders who are not yet old enough to carry weapons and limits the number of foreigners to 33% of the peloton.

On 11 July, on the BBC, an anonymous columnist chose sport to make the voice of London heard. “Today, if Mr. Hitler had agreed to let Europe live in peace, the 34th Tour de France would have set off joyfully.”

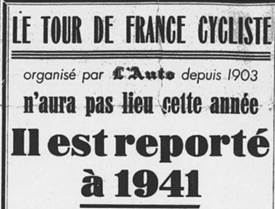

Everything seemed more or less in place, but while it was business as usual at the velodromes throughout the winter, there were great difficulties at the start of the road racing season. Paris-Roubaix, whose route was initially validated by military authorities, was transformed into Roubaix-Paris and finally saved in-extremis as Le Mans-Paris! It looked like there was also going to be course reversal for Paris-Tours, and the clouds were particularly threatening on the Race to the Sun, which L’Auto was exceptionally associated with the Le Petit Niçois newspaper in an attempt to save the organisation. Above all, Henri Desgrange published a paper with a very pessimistic tone for the future of the 1940 Tour de France. He evoked a course in the form of a “deflated bladder”, listed all the constraints he faced, and concluded as follows: “It would be enough, wouldn’t it, for you to expect this article to end with the announcement that the 1940 Tour de France will not take place? Well! It is not enough for us and we still have one last hope of being able to triumph over all these difficulties, and we want to give it a try”. The sentence was not long in coming. Four days later, the announcement was posted on the front page: “The Tour de France will not take place this year. It is postponed to 1941. See the explanations provided by its creator, Henri Desgrange, in the 13 and 14 April issues.”

Events then precipitated the country into the dark sequence of the German occupation following the signing of the armistice of 22 June 1940 by Philippe Pétain. Meanwhile, Charles De Gaulle launched his 18 June appeal on the BBC, the Free France timidly structured itself behind the “Leader of the French who continue the war”. It so happened that from London, the following 11 July, a small French enclave decided to act as if the Tour de France had started. The programme “Ici la France” was broadcast daily for half an hour on the BBC. That day, an anonymous columnist whose name remains unknown chose sport to make the voice of London heard. “Today, if Mr. Hitler had agreed to let Europe live in peace, he would have set off joyfully on the 34th Tour de France*. A completely fictitious story began, as a way to reunite the divided country and to find itself in a shared and happy wistfulness. This was far from reality, but in the legend of the Tour, the story is as important as the race.

It is unlikely that Henri Desgrange could have heard this report, which would have certainly given him chills, perhaps even drawn a few tears. For the 1940 Tour de France, even if it had been able to take place, would also have been the first without him. Operated on a few months earlier and seriously weakened, the father of the Tour de France died on 16 August, at the age of 75. His successor and spiritual son, Jacques Goddet, took over the reins of the newspaper and the following year he opposed the organization of a Tour de France whose prestige would be claimed by the Vichy regime. The return of the real Tour de France had to wait until 1947.

* Source: L’Histoire, number 354, June, 2010. 1940: The Tour de France will not take place. By Marianne Amar